(This story is the fifth in a series to celebrate the 20-year anniversary of TEF Design. Check our blog for newly published, stories about our firm’s people, our community, and what drives us to design. Sign up — in the right corner above — to receive those updates in your inbox.)

In 2004, when Tod Williams and Billie Tsien were looking for a local architect to help them build the East Asian Library at UC Berkeley, they were referred to TEF. This began a long relationship between our two firms and a personal friendship with Tod and Billie. Billie was in town a few weeks ago to give a lecture at the Asian Art Museum. The day after, over breakfast, we talked about art, architecture, politics, kitchen handles, and the Great Wall of China. Below are excerpts from our conversation.

Billie Tsien: So you’re writing a blog for TEF?

AV: We have been writing several posts to commemorate our 20th anniversary this year. It’s about our history and the founding of the firm and how it all came about. The idea is to explore a diversity of topics and formats relating to our identity as a practice and to reflect on our past and the evolution of the firm. My dad always told me, “Never ask a question the answer to which you don’t already know,” but I don’t think he’s ever interviewed anybody.

Billie Tsien: Interesting...

AV: It probably comes as no surprise to you that you and Tod are very popular in our profession. We all want to be you. It’s not just the work that you do, but how you do it and the humanity of it. I think, also, there is some personal modesty that comes through the work. Yet I know that your work is just as grinding as everybody else’s work. You devote time to projects and they last forever, and sometimes nothing happens, and sometimes things happen that you don’t predict. So how do you keep the hope and the humility in your outlook?

Billie Tsien: Well, I think Tod and I are actually both really shy people. Although he doesn’t quite project it because he’s big and he sometimes talks over people. But I think both of us cringe when we hear people say nice things about us. It’s lovely, but it’s humbling. Basically, I stop and change the subject. So what does that mean in terms of how you keep on working when a project keeps going? We’re going to have a project that will probably end up being 20 years long, that’s in India. And your fees stop, but you’re still working.

I think both of us are quite shy and we’re also stubborn. It’s a different kind of stubbornness. I would say Tod is very much kind of “grr-grr-grr.” But he has no sense of priorities, totally no sense of priorities, so he is also this same kind of “grr-grr-grr” when talking about whether the handles in a kitchen should be vertical or horizontal. Which actually drives me crazy, and it drives people in the office crazy. Because I feel like saying, “We’re supposed to be working on this project, and you just spent two hours with the client talking about whether the handles should be vertical or horizontal.” And I get mad at him, too. But that’s how he moves forward in a project, because he’s always interested and has no hierarchy of organization. I have a pretty strong hierarchy of organization. And after the first 15 minutes of the handle conversation, my mind starts to wander. And then after half an hour, I go to the bathroom and I never come back.

However, if he has no hierarchy, I have no strategy. That’s not quite true, but I’ll explain it. I think I have some sense of who the audience is and how important it is to communicate to the audience in a way that we actually understand each other. So that’s my strength and strategy. It’s not strategy like overall business strategy, where we are somewhere in the firmament of architects, high, low, I’m like a donkey tied to a pole. When you see the donkey going around in a circle—I’m that donkey and I go around in a circle. I just am putting one hoof in front of the other.

So: shyness, no hierarchy, stubbornness, no strategy.

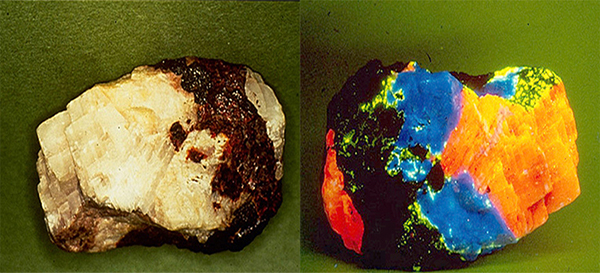

AV: The pictures of your son’s rocks that you showed at yesterday’s lecture (white rocks that look unremarkable in normal light but that reveal kaleidoscopic colors when put under UV light) make sense now. It’s that inner life, I guess.

Billie Tsien: Yeah. I would also say that perhaps one reason people can identify with us is that I don’t think most people have a strategy. And you look at certain people who seem to be very successful and you say, “They’ve figured out the whole trajectory of everything.” For most of us who don’t have a particular strategy, it’s kind of comforting to know that maybe just trying to do the best you can is all we can do.

AV: But often that kind of thinking also can lead to defeatism and fatalism. In my culture, this approach is really well developed.

Billie Tsien: Very Russian!

AV: Right, but clearly, there’s none of that in your work, and there doesn’t appear to be, from the outside at least, any of that in your life. So what’s your secret? How do you accept things that come your way without being defeated by them?

Billie Tsien: I’m probably better at this than Tod. But in terms of the way things come in your life, nothing is as important as, for example, a sick child. It’s a very fatalistic idea of how to prioritize things. But I suppose that’s how I pull back from feeling defeated, because I have a life outside of the practice. And it’s never in control, but when my personal life is moving forward, then everything else is certainly deeply important, but to me it takes less priority.

This is a generalization, but I think women have a broader sense of life. I see this in the way people work in the office. We have different strengths. Many of the men have a very focused work view. And so I think Tod’s probably more focused and feels things more deeply in terms of work. I’m not saying he’s not tortured. He IS tortured. But maybe there’s a little switch, this little “turn off the torture” switch. And I quite often flip that switch—it is also important in life and partnership. Although Tod gets really mad at me sometimes when I’m not feeling the same torture he is.

AV: You don’t turn off the switch on his timing, right? I’m familiar with that concept.

Billie Tsien: Right. And that gives your life balance. There’s a bigger world out there. I think, especially for young women in school and young women in the practice, it’s really important to say that there are other ways of doing really good work that don’t entail being like a man. Because that’s very scary. It’s not even about life choice. It’s not like I’m going to not have children. It’s like, “Do I have the personality to be like ‘blank’?” And you think, maybe I don’t have the personality, so I shouldn’t do this because I can’t be like “blank.” It’s good if there are more “blanks” to say, “Well, okay. Maybe I’m not this, but I am this.” And I think for women, in particular, there have been very narrow choices defining how you’re supposed to be, and they are quite scary, because they seem to imply a lot of other stuff.

AV: We all have opinions about recent political developments, and my question to you is, have the results of the last election made any personal difference to you? Do you interact with the world in any different way? Do you live your life differently? Are you thinking about different things? I’m not asking, “What’s going to happen, Billie?” Nobody knows the answer. But just on the personal level, has it made a difference to you?

Billie Tsien: I think it’s made a difference to everybody on both ends of the spectrum. And I guess what it has made me conscious of, and what everybody talks about, is this sort of bubble that we live in, where you think that everybody of good spirit and intelligence is in some way aligned with what you believe in. And so I feel very shaken. I’m struggling because there are some people around us who are Trump supporters and are sort of our extended family. I am struggling because I don’t know how I can talk to them.

AV: Have you found a way?

Billie Tsien: Not yet. I think Tod is much more ready to engage, but it’s in my personality to just be the Great Wall of China. I’m just behind that wall. It’s going to last for a really long time.

AV: It’s convenient you have one, right?

Billie Tsien: Nobody is going to tear that wall down.

AV: Too much trouble.

Billie Tsien: Of course, personally it’s affected me in that way. And as a member of a profession, as well as president of the Architectural League, I’ve been trying to think about what we can do to address this. Do you issue a manifesto? If you issue a manifesto, who cares? Who is reading the manifesto? So I don’t have an answer. What I try to do is understand what I can do on that sort of civic level.

I took my mother to Obama’s farewell speech in Chicago, because she is, as you can imagine, a super diehard fan. And she’s 89 years old. We got there late. I had to hustle her across a huge hotel lobby and escalators and across the convention center floor. She was trying to walk fast. I’m pushing her to go faster...

I wake up in the morning and I read every single news source. It’s not good for your blood pressure or grinding your molars down into little pebbles. But Obama talked about the long view, and how to really understand what civics means and how to be a good citizen. So these are the two poles I’m struggling with: both the individual one, in which I am really out of my mind, and also the more professional long view. I am trying to work towards the longer view. I don’t know what the answer is. That’s why I read all these things. I’m looking for answers. Wear a pink jacket, wear a red scarf, show up in D.C.

AV: Did you go to D.C.?

Billie Tsien: Yes.

AV: My daughter was there, too.

Billie Tsien: There are few heartening days. That was an extremely heartening day. As well as the defeat of the “repeal and replace” healthcare initiative. So a couple of high points in there. The saving grace is taking the long view and learning to understand civics in a broader way, so that you can participate in some way in the governance of the country and talk to a son-in-law or something like that. I don’t know what the answer is.

AV: I have completely, cold turkey, stopped consuming all media.

Billie Tsien: How can you do that? That’s impossible.

AV: It’s totally possible, and it does wonders for your blood pressure.

Billie Tsien: I have high blood pressure. The doctor said, “What happened to you? Your blood pressure is so high.” And I said, “What do you think?” And so she said, “Okay. Well, you have to start taking these pills.” And so maybe you’re right. But that’s like telling me I can’t breathe. What am I going to do? I’ll be twiddling my thumbs.

AV: Do you find that your engagement with the media now is any different than it was before?

Billie Tsien: Yes. I never used to wake up in the morning and read Politico. And Talking Points Memo, and then Huffington Post for the gossip, and then The Hill. I did the exact opposite of you with media consumption. And I will take your advice to certainly pull back on it. I do feel like there needs to be some sort of personal engagement to understand what the issues are, though. But I think, clearly, I’m swimming in my own pool with my own swimming friends. I still can’t bring myself to read Fox News. Then my blood pressure will make the top of my head explode.

AV: It might put you out of your misery...

Billie Tsien: But I do take your advice seriously, too. I can’t eliminate my media fix, but I can truly try to reduce it, because it’s compulsive. And it doesn’t actually lead to action. It only just leads to, obviously, some sort of drug that I’m just taking to make myself feel better, which is why people have drug problems.

AV: Right. You have to have more.

Let me ask you some questions about art. Every time I hear you speak, you mention an artist. Yesterday it was a photographer, and then a dancer at the end. Most of the time, not always, these are people I’ve never heard of. You seem to have a very well-developed knowledge of what’s going on in the modern art world.

I have two questions about that. One is, when you were growing up, was there a culture of art consumption in your house? Not necessarily visual art, but the arts, generally. And the other is, how do you find out about stuff? Do you just follow your instinct and your tastes? Or do you read somebody that points things out to you? Or is it just because you live in New York and everybody comes there? How does it work?

Billie Tsien: Well, growing up, there was always classical music in my house, and I’m a classical music dunce, but there’s a lot that’s familiar to me. And my mother played the piano all her life but now is taking serious piano lessons. It’s very good exercise mentally and physically. She would also take us to art museums. I think her interest is deepest in music—she goes to concerts all the time. But it was very clear to us kids that culture was another world, and if you were going to be an interesting person, you had to find pleasure in this other world. So, for me, there are worlds, whether it’s art, music, dance, or literature, really reading, that are parallel activities with architecture.

Since we’re not doing it, clearly, these other worlds are not equal, but that kind of interest and draw for me is. And so in terms of all of these cultural experiences, Tod and I both have pretty much the same hunger. Although, because he’s so focused, I’m the person who says, “We need to do this, we need to see that.” I sign up for the subscriptions. But we love it. We always play a game every time we walk into a gallery space or a museum. We ask ourselves, “What is the one thing we would steal here?” We walk around, and then we look at each other and we say, “That’s the one we would steal.” And usually our choice is pretty consistent. It’s a very deep response.

Take the young photographer John Edmonds. We went to an art fair in New York. It was one of the small shows, not a big show, and we saw his work hanging there. And we actually bought a piece from him, because it’s both so powerful and so gentle. It’s called the Do-Rags series. It’s printed on silk, on a really diaphanous silk. So it’s both like a punch in the face and a hand that touches you. We saw it and it was amazing.

AV: Do you know him personally?

Billie Tsien: He was there. He’s very young. But he’s one of those Yale wunderkinds: out of grad school and straight into the gallery. Peripherally, it’s a very important way of feeding our work. It so much easier to be inspired architecturally by things that are not architecture. If we look at another building, our response is usually just, “Oh.” I don’t mean that to be a put down, but, generally, it’s very hard to get ideas, at least for us, about architecture from architecture, because someone has already had that idea and made it happen. You can think of variations. But if you look at something else, it allows you to think in a deeper way without the connections and the baggage that goes along with looking at architecture.

And how do we find out about things? Sometimes we might get a recommendation from someone in the office, but it’s mostly a consequence of living in New York. I’m constantly scanning the listings for things to see. Of course, I don’t see a lot of things that are not in New York, or even that are not on a more or less established path. There are so many galleries that I want to look up on the Lower East Side. It’s hard to cover everything. Maybe it’s a more constructive use of time than waking up and looking at Politico.

AV: What about travel? I know you travel all of the time. You flew here for a day to talk to 200 people. My wife said to me last night, “That is such a generous thing that she did, to come all this way and talk in front of these people.” Because we can all go see your buildings, but it’s impossible in any other way to hear you talk about them. And it’s very meaningful.

Billie Tsien: I truly feel honored that people came out. I feel really honored to be asked to talk. So I don’t feel that it’s generous. I feel that the offer, and people asking me to speak, is generous.

AV: I know you travel a lot for work, but you must also travel sometimes for fun. So I wonder if you’ve been recently to a place that you found particularly remarkable.

Billie Tsien: I have truly been to some amazing places. A month ago we took 10 days and went to Hawaii. For me, that was a remarkable place. It’s partly because of what I spoke about last night—being Asian-American and being a part of the mainstream culture, but at the same time not being a part of it. And I feel like the islands of Hawaii are exactly that. It is the one place in the world that I feel completely comfortable.

There are times when I’ve been to China and I don’t know what’s going on. I can’t speak the language. I know I look Asian, but I just don’t get the culture. Of course, I feel comfortable in the US, this is my country. But on the East Coast and certainly in the Midwest, I sometimes feel like, “Whoa. I’m the other in the room.” I’ve also been in situations where people maybe don’t see me as “the other,” when they say, “Well, we’re all white here.” I want to say to them, “Actually, no.” But Hawaii is an extremely comfortable place. I’m truly, as I said, an indoor person—but there’s a deep sense of the power of the landscape in Hawaii, the sort of gods of the landscape and of the land. I don’t know enough about them, but you can feel it. And so my shoulders come down. They probably drop about six inches. And I just feel very, very peaceful.

AV: Is part of it because there are people on the street who might look similar to you?

Billie Tsien: Yeah. It is that combination of being American and being Asian. The fact that our son is what they call hapa is our ticket to pretending that we actually live there, because people just assume he does. It’s because of that kind of in-between state that I think Hawaii is the one place I feel at home.

AV: Well, your work, also, I think speaks to that kind of in-between quality. The moments that I enjoy most about your buildings are moments of repose and the moments of the bench here and the wood rail here or there, and the light coming out from somewhere.

Billie Tsien: Wasn’t that a nice thing that that woman said about the East Asian Library? That it feels warmer when it’s raining. That made me so happy. But weren’t you worried she was going to say it’s leaking?

AV: I was...

You collaborate with people a lot. In 2004 you came to TEF and talked to us. You must have developed a way to assess who you want to work with on your buildings. How do you decide who you would like to work with? And what did you think of us when we met - what made you want to work with us?

Billie Tsien: Well, I guess the first thing is, you sense that there’s a similar culture in the studio and in the people. And at the simplest level, you ask yourself if you would want to be friends. And I’m not the person who is doing it—but next you look at the drawings and the quality of the drawings. But it really has a lot to do with the sense of that connective culture. Now, that’s not always true. Sometimes there is a culture that might seem not necessarily corporate, because I don’t think we could bridge that gap, but more business-oriented. That wasn’t TEF. I think with you it was more that we felt we could be friends. And then, as I said, the quality of the drawings.

AV: I remember when we had a crisis in the beginning of construction administration, when we all realized that we just didn’t have enough money. And Doug and I had a conversation with Tod and Jonathan on the phone. Tod was very straightforward about the financial aspects of our work. He said: "I understand about the money. And if you want to walk away, walk away. But if you’re committed, you’re committed.” That resonated with me and with Doug.

We were all so committed to making this the best building possible, that initially I was missing that other aspect, which is that it's a group endeavor. There’s a bunch of people involved. I probably learned more from that part of the experience, the group endeavor, than from anything else on the job. I'd like to thank you for that.

Billie Tsien: It’s interesting to understand the dynamic between being demanding and understanding when everybody is trying to do their best. What is the level of demand? And what’s appropriate at a particular moment? That, I think, is a really difficult thing for young architects, because they don’t know how demanding to be. Do you agree to everything? Where do you draw the line? What’s the important line to draw? What are the other lines you can let go? When do you learn from the person who actually made it?

I think that’s a result of a lifetime of being an architect, because it changes every single time. How do you set your criteria? In many ways I think you’re a master at that. I think it has to do with a personality. Some people’s personalities will never allow them to be effective supervising construction.

With my personality, I would let go of the line. But Tod’s personality is such that he would be really forceful about some things. As time has gone on, he has realized that you sometimes have to let the line go. So he’s a little bit more malleable these days. There was a guy named Martin Finio in our office. He was amazing at finding the right line, and in the end, everybody felt joy. I think that you are masterful at finding that line. And having an incredible logic, but also keeping people feeling proud about what they’re doing.

AV: Oh, I think it’s critical. It’s so important. This whole idea that we don’t have craftsmen anymore.

Billie Tsien: That’s not true.

AV: It’s not true at all, no. You just have to give people half a chance to be proud of what they do.

Billie Tsien: Absolutely. We were talking with some students at IIT, and one woman said, "You talk about craftsmanship, but that's really elitist, because only the rich can afford it. And the craftsmen don’t live it and are dying out. Things need to be 3D printed.” And Tod said, “If you’re a great plumber, you are a craftsman.” It’s not necessarily some guy sewing a leather chair. It has to do with pride.

AV: That's right. Billie, this has been a really great!

Billie Tsien: Well, it was actually just a nice conversation.

AV: Yeah. We should all be so lucky that our life is just a series of nice conversations.

Billie Tsien: Yeah. Thank you.