Collaboration has been central to the practice ethos of TEF from our earliest days, starting with our work with Simon Martin-Vegue Winklestein Moris on a day school and later, the transformation of the Ferry Building in the late 1990s, and continuing today. We invited three of our current partners to talk about what collaboration means to them, how they navigate it, and what role it might play in their futures.

With Sam Miller, FAIA, partner at LMN Architects in Seattle, we’ve been collaborating on the City College of San Francisco Diego Rivera Theater at City College of San Francisco for more than a decade, including the Performing Arts Center and Precinct Plan. We’re also partners with LMN on the new North Field Academic Building at the University of California at Berkeley, currently in design development.

Our partnership with Tatiana Bilbao, chief executive officer of Tatiana Bilbao Estudio in Mexico City, on PG&E’s Hunters Point Substation in San Francisco, marks TEF’s first international collaboration. Tatiana was completing work on the Hunters Point Vision Plan in 2017 when we were approached by the utility giant about collaborating with her as the architect of record for the new electrical facility.

We’ve collaborated with E.B. Min, founder and principal of Min Design in San Francisco, on a variety of projects for the past nine years, as part of consecutive term contracts with San Francisco Public Works. Our joint venture has tackled everything from feasibility studies to municipal facilities upgrades, including our current work to renovate the Mission Cultural Center.

Q: How does collaboration with other architecture firms fit into your practice?

Tatiana Bilbao: I really like to collaborate, and we collaborate on many levels. There is no truth to the idea that architecture is created by a single mind. It has never been. It’s a collaborative act. Bringing specific people for a specific project, it’s very important, because it adds a lot of richness to making architecture. If the idea just comes from one individual, then I don’t think it truly responds to the collective needs to serve.

Hunters Point Team members (left to right, Tatiana Bilbao, Paul Cooper, Kerstin Roeck, Jonathan Manzo, Gregg Marioni, and Darin Cline) visit the Willis Concrete Construction site to inspect the custom exterior concrete panels specifically fabricated to mimic organic variation and imperfection.

E.B. Min: My practice was originally a partnership between myself and Jeff Day, and we were located in San Francisco and Omaha. We always had a long-distance partnership, and by nature, that means it’s a collaborative relationship. There’s something that you gain in collaboration, where you get exposed to more ways of working, more ways of thinking. Collaborating on design can be super fun, like you’re playing a game with people, or you’re at a dance and you get to dance with different people. So I’ve always liked collaboration, because I want to hear what other people think, and I want to hear what they think about what I’m doing.

Sam Miller: As a single office that works across the country, we’ve always needed to collaborate with architectural partners, and we enjoy collaborating. It’s a key piece of the success of our work. Every collaborator brings unique strengths and connections to the community and perspectives that we really value. And we are flexible in how we structure the partnership, because every project is different, every client has different expectations, and every partner is a little different in the strengths they have to offer.

Q: How do you know when a potential partner is a good fit?

Min: I just have a gut feeling, right? It’s like going on a date: are you asking me questions about me, or are you only talking about yourself? Because that’s always a red flag. And of course, you look at their work. But I also listen to how people talk about work, how they talk about the project, and how they talk about the relationship they envision. All of these things help me decide whether or not a collaboration is going to be successful.

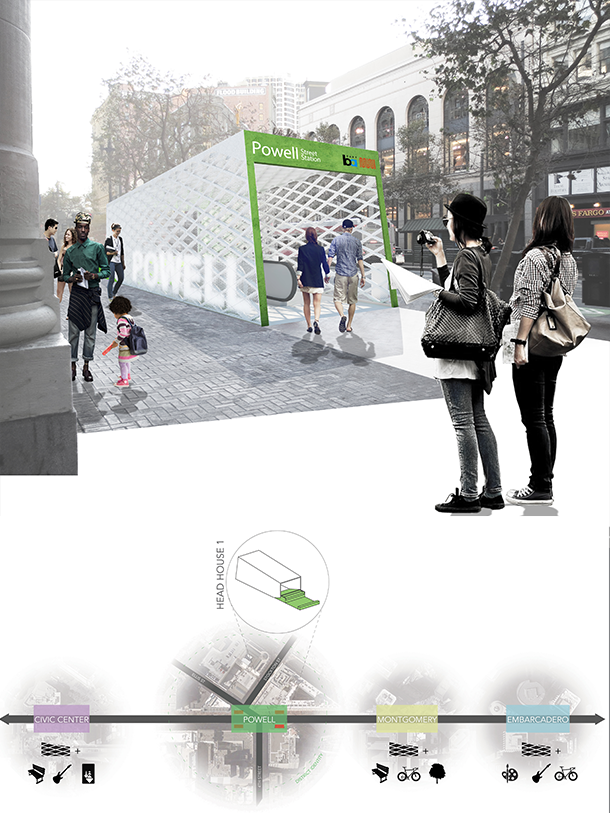

In addition to TEF’s joint venture with Min Design to service a wide range of projects for San Francisco Public Works, we collaborated on a concept for new BART/Muni entrance enclosures along Market Street. The award-winning design encompassed a kit of parts approach to each station that could support the distinct culture of its location.

Miller: Before the pandemic, we spent a lot of time traveling as part of our pre-positioning for a project. We’re meeting with numerous potential collaborators to talk to them, ideally have a dinner together, to understand them culturally. We want to find partners who can successfully complete the project with us, but who are also a joy to work with, as passionate and committed to doing great work as we are. I’m a big believer that the social results in the physical in architecture; that it’s the strength of relationships that literally create the physical outcome. A lot of it boils down to chemistry. That’s the secret sauce that makes a project work; there’s a real connection. Trust is important, and shared values—not the same values, but at least a common aspiration of what we’re hoping for with the project. That’s why meeting people, ideally in person, is important—to get to know them, to spend some time together in a nonprofessional setting to see if you have that connection and chemistry.

Tatiana, because you work around the world so much, what’s your perspective on working with architects in the United States?

Bilbao: I think that it’s harder to collaborate in the United States for many reasons. This is the only society where I have worked that isn’t a welfare state. Because of how it’s constituted, the philosophy behind it is that the country is going to create a platform for you to succeed, but you have to then take care of yourself in every other regard. That is promoting a very competitive and individualistic society. Whereas my country and countries in Europe are welfare states, so our understanding is that we need to collaborate with the other in order to be able to take care of ourselves, by paying taxes and having services that are built upon our communal effort, like hospitals, infrastructure, education, etc. That creates a different notion of collaboration. Our collaboration with you is my first very successful collaboration in the United States.

Rendering of the PG&E Hunters Point Substation (top). Principal In Charge Paul Cooper of TEF and Tatiana Bilbao (standing) share details of the project’s development with TEF staff during a private tour of SFMOMA’s “Architecture from Outside In” exhibit of her studio’s work earlier this year.

Q: Tell us about your experience collaborating with others and with TEF.

Miller: Right from the get-go, with our City College of San Francisco project, we found a really good synergy and connection with TEF. Each firm had a high level of respect for the other. Early in design and schematic design, LMN was leading the design effort from our Seattle office, and several members from TEF came to live in Seattle for about six weeks, fully embedding within the team. It was a chance for both firms to act as a single entity, to see how we each work, and to understand our priorities for what we were trying to accomplish with the project. It was a great opportunity for the TEF team members to immerse themselves in our design approach. That’s where these collaborations can be really successful, there’s a complete blending of the team, and there isn’t a differentiation between who’s from which firm. We don’t get to co-locate like that every time, but when we can, it’s terrific. We became friends over the course of the project.

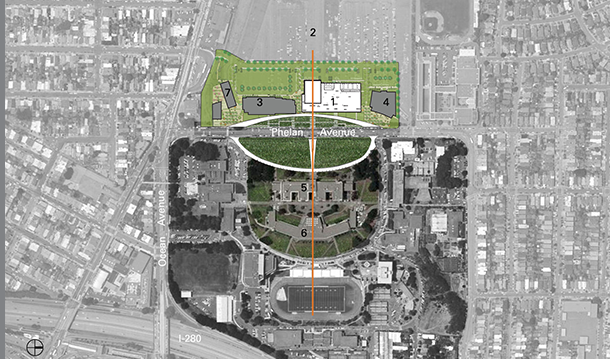

Our partnership with LMN at City College of San Francisco over the past 15 years has evolved along with the design of the Performing Arts Center - now known as the Diego Rivera Theater - to its preliminary concept (top). Early on, we also collaborated on the precinct plan for the campus’ westward development over the Balboa Reservoir, organizing the theater and adjacent structures around a green commons that reinforces the formal structure of the campus’ original design.

Min: I was excited when TEF asked us to partner with them for the Department of Public Works contract nine years ago. I liked that we would get to work with a firm that was larger and more established. And we hadn’t had exposure to working with the city before, so we would get to learn about best practices for working with municipal agencies. There was a mentorship aspect to the relationship. But then we brought to the table our design ideas and our skills in design communication and presentations. At this point, I feel like our relationship has evolved.

With other projects that we’ve been working on, like affordable housing for Hunter’s View Phase 3 and Balboa Reservoir Block F, both with David Baker Architects, there’s also mentorship going on there too, because we haven’t done affordable housing projects or multifamily housing at that scale. They wanted to work with us because of the design thinking that we bring and the point of view that we have. It’s been a mutually respectful and beneficial relationship.

Bilbao: In general, we have had really great experiences, with one exception. The local architects assigned to us had a lot of interest in the client, and they prioritized that over the collaboration. The client would approach them directly about making changes, and the local firm would just make the changes without telling us. Collaboration has never been as successful for us with local architects as it has been with TEF. You really are mediating between the interests of the client and our interests, and you understand how to balance those things to make us both happy. When the client wanted changes, you would come back to us, and I knew that the decision you made would be right. I trust your firm 100 percent. Collaboration is trusting that the other person has your interest in mind. The most important thing is trust, but the second most important is to always listen to each other.

Q: How is collaboration continuing to play a role in your firm’s future?

Min: I really like working with other people and other firms, as long as we all have the same shared goals. And even if we are the only architecture firm involved with a project, I like having other design disciplines on a team that can really engage with us, whether it’s landscape architects, lighting designers, the engineer, everybody. We want to work with people who have an opinion, but who all understand how to work together. It always makes for a better project. A collaborative proces is much better than saying, “Here’s my set of drawings, and I want you to do this.” And within our office, too, I feel like I really do want to hear what people have to say. I want everyone to feel free to say, “I don’t think that looks right.”

TEF staff at the Seattle offices of LMN for a recent team meeting.

Bilbao: In every project, even if our office is the prime, there are always different consultants coming in, there are the clients and other decision makers. We feel they are all members of the team. We encourage the process to be very horizontal. When we do projects abroad, or sometimes larger projects in Mexico, like the Mazatlán Aquarium or the University of Monterrey, we collaborate with other offices. And we love to collaborate more than once with the same firms when we can. I haven’t had the opportunity to do so with local architects yet, but I have with other subconsultant firms.

Miller: A really big change that’s happening right now is the move toward integrated delivery. More and more, clients are looking for design and construction teams to be more fully integrated. The old idea of the architect in a black cape swooping in and waving their hands, and then the team responds, is really outdated and not the best way to make projects happen. We’re interested in fabrication and in blurring the lines that distinguish design from construction. The technology is providing an opportunity for us to get more engaged in how things get made, collaborating with not just general contractors but subcontractors, fabricators, vendors, materials suppliers. So it’s going to be more and more critical to have the capacity to connect with one another.