To me, preservation isn’t just about rejuvenating a part of the past. It’s also about transforming the present. Historic buildings can provide a lot of character in a new neighborhood. They add layers and texture, providing the sense of authenticity and connection to the past that people long for and that makes a place unique. Even if the building is not in great shape, it can be worth renovating to provide personality and excitement that can help energize an entire neighborhood.

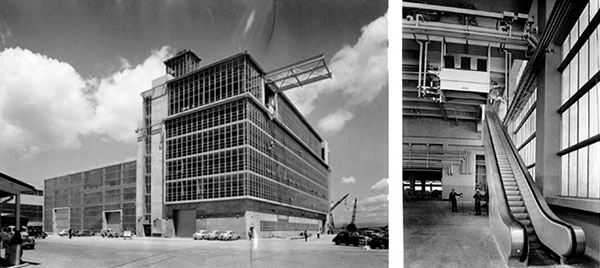

Historic Photos of Glass Works, courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Older buildings that provide character and make for interesting, airy workspaces is key to the draw of San Francisco’s South of Market and Mid-Market neighborhoods to technology and start-up companies. I worry when I see new developments plans that turn their back on older buildings that can impart variety, vitality and a sense of identity. One such missed opportunity in San Francisco is the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, and particularly the extraordinary Ordnance and Optical Shop Building. Known as the Glass Works, it was one of the first all-glass curtainwall towers—two acres of glass in all. Designed by Ernest Kump and completed in 1948, it has huge floor plates, and it’s right on the water. You just can’t build that kind of structure new anymore. Unfortunately current plans for redeveloping Hunter’s Point Naval Shipyard call for demolishing pretty much all of the old industrial buildings on the site, including this one. It has tremendous potential to be adaptively reused, would have amazing views and spaces inside, and would add a lot of value to the development.

Consider Ford Point across the bay in Richmond, where a developer was willing to rejuvenate a 1930s automobile assembly plant designed by Albert Kahn into a complex with an event venue and office space. The event venue, Craneway Pavilion, has hosted everything from an Oktoberfest Festival to the Bay Area Roller Derby Girls championship to a Björk concert. One office tenant, a solar panel manufacturer, put photovoltaics on the building’s distinctive sawtooth roof, creatively linking the past with modern technology.

New Mission Theater Before and During Construction

The return of the historic New Mission Theater in San Francisco at 2550 Mission Street is another example. Originally a nickelodeon, it was turned into a theater with the addition of an auditorium and new lobby by the local Reid Brothers architecture firm in 1916. Then in 1932, Timothy Pflueger was brought in to modernize—Moderne-ize?—the building. He added the 70-foot tall neon vertical fin outside, as well as an outer lobby and staircase. In 1993, the theater closed and remained empty. City College bought it with plans to demolish it for a new campus, but preservationists rallied and got the building listed on the National Register of Historic Places and made a City Landmark.

Now in the hands of Austin-based Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, it’s undergoing a renovation that will restore the main theater and add four other screens by bringing the lower balcony forward 15 feet, keeping the original ceiling intact. Alamo Drafthouse plans to show a mix of classic, indie, and foreign films, as well as events. Like the Sundance Kabuki Cinema, you’ll be able to buy dinner and enjoy it with a cold beer in the comfort of your seat. This is a great model for preserving old movie theaters in a way that works economically. There aren’t any movie theaters left in the southwest part of the city, so it will fill a huge gap, not to mention bring back to life a beautiful building as an iconic presence and community gathering place on Mission Street.

Just as historic buildings can galvanize new development, new buildings can also bring energy to historic districts. I serve on the San Francisco Historic Preservation Commission, and one of the more interesting recent projects we’ve reviewed has been the new Apple store. Apple put forward a design for a new flagship store in Union Square last year, a minimalist box that we thought was too minimalist for a street with so many historic buildings. For one thing, it presented an unrelieved 44-foot-long wall of glass on Stockton Street. Initial plans also called for the removal of artist Ruth Asawa’s distinctive fountain from the 1970s, a bronze sculpture that depicts scenes of San Francisco contributed by 250 friends and school children.

After an outcry, Foster + Partners reworked their design, keeping the fountain more or less where it is, adding vertical steel columns to the Post Street side for texture and scape, inserting an eight-foot-wide glass band along Stockton to create transparency, and transforming the existing but banal plaza. The new plaza is larger, better-shaped, and well landscaped. Union Square’s historic district guidelines require new buildings to be compatible and have a sense of massing and scale and texture that plays well with the older structures. Apple’s new building is still decidedly contemporary, but it works well with its neighbors.

That’s just the kind of synergy that San Francisco needs. Too often in this city, preservation is pitted against new construction. We’ve got a lot of great historic structures, and we’ve got a lot of room for creative newcomers. It’s a good time for both sides to put down their arms, declare a truce, and see the value that each can bring the other.

After all, isn’t turning swords back into plowshares just another form of renovation?