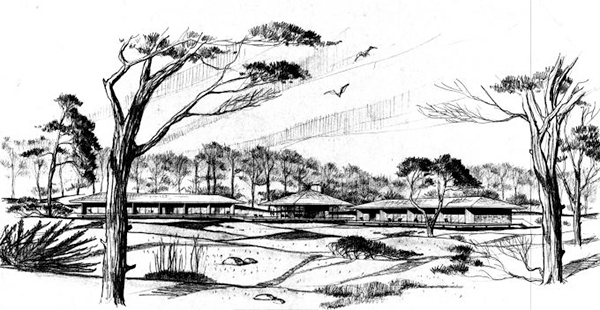

Pictured Above: Surf and Sand from living room, California Department of Parks and Recreation Asilomar Historical Archive Collection

TEF teamed up with architectural historian, preservation planner, and writer Bridget Maley to create a series of historic structure reports primarily focusing on John Carl Warnecke’s 1950s and 1960s additions to the Asilomar Hotel and Conference Grounds in Pacific Grove, California. Bridget focused on historic research and crafting a chronology, while TEF principal Andrew Wolfram focused on the technical recommendations. Other contributing team members included Architectural Historian and Photographer Shayne Watson, Historic Landscape Architect Denise Bradley, and Structural Engineers Tuan & Robinson. We sat down with Bridget and Andrew to talk about their collaboration on this historic project by an underappreciated master of midcentury modernism.

Q: How did this project come about?

Bridget Maley: Under the agreement between California State Parks, which owns Asilomar, and Aramark, the concessionaire running the facility, Aramark gives California State Parks a certain amount of money each year to fund long-term planning. California State Parks decided to be proactive about the Warnecke buildings and so commissioned these historic structure reports. They know these buildings will be targeted for an upgrade soon. Essentially, little has changed since they were constructed.

Andrew Wolfram: Which on the one hand was great, because the buildings have an incredible level of historic integrity. But they were also deteriorating, and they’re special buildings, especially in the context of all of Warnecke’s work. Incredible all-glass pavilions, open to the landscape, with exposed structures.

Surf and Sand Living Room, Shayne Watson, Photographer

Maley: We were asked to look at seven buildings—several of the Warnecke complexes and two of the Julia Morgan buildings that had been studied before but needed an update. We also completed a report on a small cottage, acquired by Asilomar in the 1970s, that has ties to John Steinbeck. The idea was to plan for the eventual upgrade of each of these complexes and structures.

Q: Julia Morgan planned and designed Asilomar’s original campus in the 1910s and 1920s, which had already been designated a National Historic Landmark (NHL) Historic District in 1987, is that correct?

Maley: Yes. In the 1980s, Warnecke’s contributions were only about 25 years old, so they were not considered in the NHL designation. After completing the historic structures reports, we’re recommending the NHL be amended to include Warnecke’s contributions to this important site. He had a vision of how to take what Morgan had started and expand it with a modern sensibility.

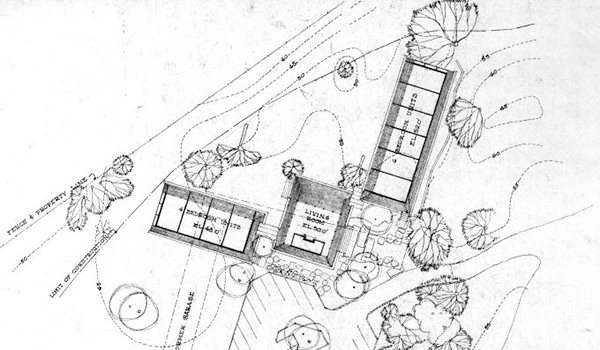

1958 Warnecke Perspective Drawing and Plan, California Department of Parks and Recreation Asilomar Historical Archive Collection

Wolfram: We looked not only at the residential buildings, but also some of the service buildings, the Corporation Yard and the laundry facility, both of which were also designed by Warnecke.

Maley: They called the laundry building the housekeeping headquarters. It has a little break area for the housekeepers. It's a nicely designed little room, almost completely intact.

Wolfram: It’s an indoor/outdoor space, and it connects to the deck, which was originally designed around one of Asilomar’s Monterey Pine trees, sadly gone now. The Corporation Yard was also well thought out in terms of a work space, with great details in the rafters around the building, at the edges.

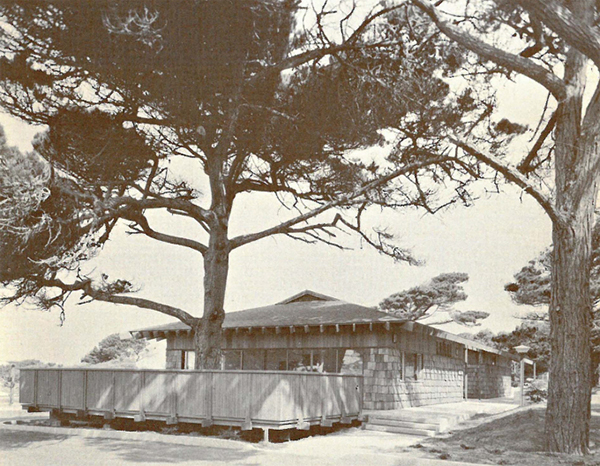

The Housekeeping Building, California Department of Parks and Recreation Asilomar Historical Archive Collection

Maley: Unfortunately, on those two buildings, the rafter tails had deteriorated so much at one point that they were lopped off. So they look sort of funky and truncated.

Wolfram: We’re recommending that the deteriorated rafter tails, decks, and built-in exterior elements be repaired. And that key elements be restored at Warnecke’s first complex at the site, Surf and Sand, which also has wonderful indoor outdoor flow. The ceilings in this complex are wood inside and extend outside as eaves, but at some point, the underside of the eaves was painted, which disrupted the continuity of indoor and outdoor experience. We’re recommending stripping that paint and leaving it unpainted, as originally intended.

Q: What surprised you when you were doing this project?

Wolfram: I think for me the surprise was just how incredibly intact these buildings were. The meeting rooms, the fireplaces, the hardwood floors, the concealed chalkboards integrated into the board and batten walls, the heating registers, the light fixtures, the dressing rooms with built-in drawers, the shoe racks, and the screen walls are all still there. That’s really unusual in hospitality projects—usually, they have been remodeled every ten years. The Warnecke buildings had been remodeled a few times, but the changes were pretty minor.

Maley: Going into this project, I knew that I liked these buildings, but after we made our first site visit, we really understood how Warnecke was taking the whole site into account. In his 1958 master plan document, he says, very straightforwardly, “it is important that any additions to the building group be accomplished without destroying the easy relationship of buildings to land. The site should not become crowded.” I always knew he valued contextualism, but I didn’t realize it was such a big part of his approach. In looking at other projects of his, I realize this is really a theme.

Surf and Sand Guest Room with painted undereave, Shayne Watson, Photographer

Wolfram: Another thing that was interesting for me was that the different complexes reflect the different time periods they were built in. The first complex Warnecke designed, Surf and Sand, was a pure modernist concept. The buildings were all glass, which is beautiful, but because of the glare and the heat, it’s not that practical for meeting rooms. With his next complex, Sea Galaxy, you can see that he was learning from what he’d done, modifying the details to create more functional spaces. The meeting rooms there are also glassy, but they’re not all glass. In Sea Galaxy, the detailing became more robust than it is at Surf and Sand, where the roof structure is very thin, which does not work well in that marine environment. Sea Galaxy has held up better than Surf and Sand because it’s not quite so delicate.

Sea Galaxy, Shayne Watson, Photographer

Q: Would say that Warnecke is due for a reappraisal?

Maley: Absolutely! His concepts about inserting modern buildings into established urban or park environments and creating contextual places and spaces are really important, but overlooked. He didn’t just plop new buildings on a site. He was thinking about the whole picture, and what that meant in relationship to what was already existing. I know other modernists were doing this, but Warnecke really had good handle on this, and executed it well.

Wolfram: Warnecke today is mainly associated with the monumental work he did for large government and institutional clients, like his Federal work in Washington around Lafayette Square and buildings like the Meyer Library at Stanford. But he also did projects like Asilomar and the McHenry Library at UC Santa Cruz, which were very thoughtful works with great sensitivity to the site. So yes, I’d say its definitely time for a reappraisal, and it would be great if someone embarked upon a serious study of his work.