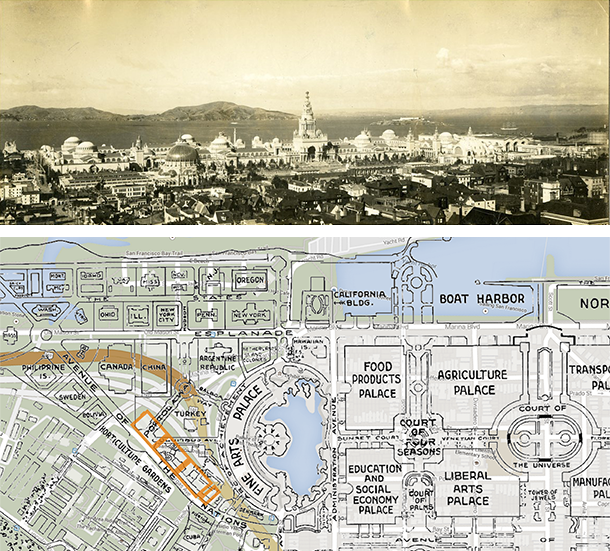

Circa 1922, Photo Credit: Image courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, 342-FH-3B16796.

Right across Presidio Parkway from architect Bernard Maybeck’s iconic Beaux-Arts masterpiece from 1915—the Palace of Fine Arts—sits a double row of six long, narrow wooden army warehouses that are nearly as old. Like matchsticks next to a music box, they are a stark architectural counterpart, plain workhorses next to Maybeck’s ornamental ode to Roman ruins. The Gorgas Rail Complex, as it’s now known, dates back to 1919 (a seventh, smaller administrative building was added to the complex in 1940). Like the Palace of Fine Arts, these structures were never designed to last. But they have stood the test of time much better than their elegant counterpart, which had to be completely reconstructed in the 1960s. We recently completed a core and shell renovation of four of the buildings to accommodate office, health, and fitness uses, and in doing so, we had the opportunity to contemplate their paradoxical endurance.

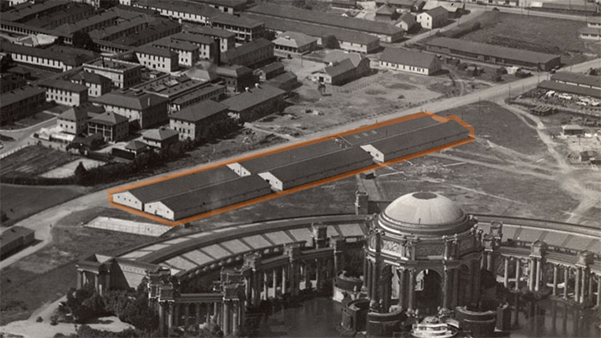

Golden Gate NRA, Park Archives, D.H. Wulzen Photo Collection, GOGA 18480.026(top). Overlay of the Expo and existing plans (above) depict the alignment of Gorgas and Mason with the Expo’s Avenue of the Nations and Esplanade, respectively, the latter featuring rail lines that were likely repurposed for the rail line linking the Presidio with Fort Mason.

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 was San Francisco’s way of announcing to the world that the city had bounced back after the 1906 earthquake and fire. Built largely on fill, the exposition sprawled across a 636-acre site, including parts of the Presidio and Fort Mason, and featured a 435-foot-high tower covered in sparkling jewels, a variety of exhibit palaces, amusement park rides, the Liberty Bell (on loan from Philadelphia), and a miniature reproduction of the Panama Canal.

After the exposition closed, most of the structures were torn down as intended, but the community deemed Maybeck’s palace too beautiful to destroy.

Gorgas building 1163, circa 1936, Photo Credit: Image by U.S. Army, courtesy Golden Gate NRA, Park Archives, GOGA 39814.

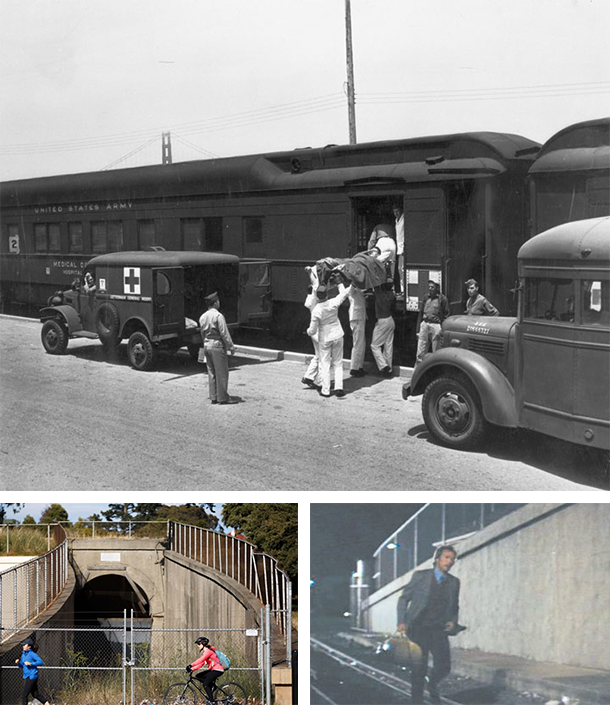

Meanwhile, the U.S. Army repurposed the exposition’s railroad tracks in order to link the Presidio to Fort Mason and beyond, then constructed the six warehouses between Gorgas Avenue and the rail line in 1919. The abandoned Fort Mason Railway Tunnel — infamously featured in 1971’s Dirty Harry — remains today. These buildings housed medical and other supplies for the army for decades —one was later converted into a library and library depot, shipping books to soldiers overseas. The palace served a variety of roles as well, from military storage depot to telephone book distribution center to temporary fire department headquarters.

Trains, like the “Army Hospital Train” (top, circa 1944), that once ran through the now abandoned tunnel (above) linking the Presidio to Fort Mason were supplied by the Gorgas buildings through two world wars. Top Photo credit: Image courtesy Golden Gate NRA, Park Archives, GOGA 35256.420.

By the 1960s, however, the palace was crumbling—as Maybeck had intended. After all, its walls were wood frames covered with nothing more than a blend of plaster and burlap-like fiber. It was saved only because the nonprofit Palace of Fine Arts League formed to raise money (helped by a $2 million state grant matched by a gift from local philanthropist Walter S. Johnson) to tear it down and recreate it with more permanent materials.

The warehouses, meanwhile, stayed in pretty good shape, despite occupying soft soil. Built using post and beam construction, the structures are elevated three feet above grade on footings below each column. These are hardly robust buildings, but because they touch the ground so lightly, they have proved resilient, riding out earthquakes and settling down like rafts on choppy water.

Gorgas building exterior. Photo by Brian Vahey, courtesy Presidio Trust.

Three of them had been renovated already about 15 years ago, and the Presidio Trust, the federal agency that co-manages the Presidio in partnership with the National Park Service, leases them to health, office and fitness tenants. A few years ago, the Presidio asked TEF to renovate the remaining four—three of the 1919 warehouses and the small 1940 one — with an eye toward office or wellness tenants. The buildings may be simple, but they have qualities that companies currently prize: open interiors, high ceilings, exposed beams, historic hardwood floors with scars intact, and plenty of natural light coming in through the windows and (except for the 1940 office building, which has dropped ceilings) skylights.

Gorgas building adaptive reuse, nearing completion

The three 1919 buildings have foundations similar to the ones renovated 15 years ago, but the building code has since become stricter. We added grade beams—reinforced concrete beams—to each gable end. On the interior, at each end, we replaced the footings below each column. Above grade, we sistered rafters and added plywood shear along the perimeter. The floors were so robust that we didn’t need to strengthen them. We also upgraded the electrical, heating, and ventilation systems and put in new lighting. We tucked the forced air heating and cooling system into the truss spaces on elevated platforms, because we couldn’t put anything on the roof without compromising the historic integrity, and we didn’t want to take up precious square footage below. The loading docks will be refashioned into public pedestrian paths.

Unlike the Palace of Fine Arts, there was no community outcry over the Gorgas warehouses’ fate to galvanize donors and spur the state to offer a matching grant, and there was no multimillionaire to step in as savior. The Presidio Trust’s mission is to preserve the history of the site while remaining financially independent and operating the park without support from taxpayers. Our renovations were straightforward, balancing cost considerations with the need to meet the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties. We made simple, restrained interventions to adapt these buildings for their new uses.

Gorgas Rail Complex, today. Photo by Charity Vargas, courtesy Presidio Trust. (cropped from original)