This is the second of three posts about the integration of artwork — and the artists behind them — into the newly renovated Garfield Center (a joint venture between TEF Design and Paulett Taggart Architects) and its role in the development and sustainability of culture and community.

Interdisciplinary artist, cultural organizer, and social justice advocate Favianna Rodriguez in her Oakland studio

Interdisciplinary artist, cultural organizer, and social justice advocate Favianna Rodriguez in her Oakland studio

As part of PTA/TEF’s renovation of the Garfield Center in the Mission District, the San Francisco Arts Commission invited artists to submit proposals to create a 113-foot-long glass mural along one wall of the natatorium. Oakland-based artist Favianna Rodriguez won with her proposal, Santuario, which celebrates the long presence of Latinx families in the Mission District. Her colorful glass artwork depicts a mother with her baby, two children swimming, and a paletero (ice cream cart vendor), as well as water and beach imagery. We asked her to talk about the origins of the piece and the role of artists in building community and addressing social justice.

What inspired you to create this mural?

I grew up in an immigrant Latinx family in Oakland, California, and a lot of our leisure time was spent going to events in the Mission District, so I have a very strong attachment to my sister community. Because I live in the Fruitvale neighborhood, which is the Latinx immigrant community in Oakland. I’ve always had a deep love and appreciation for the Mission and was very sad to see how gentrification pushed out a lot of Latinx immigrant families over the last 20 years.

When I heard about the competition to create public art at Garfield Center, I thought it would be a great opportunity to celebrate the Latinx community and the immigrants of that diverse neighborhood. As an artist, my goal is to portray communities of color and their stories, stories that have been sidelined and marginalized for too long.

In the piece, I included a mom with her baby, two children playing in the water, and an elder. When I held community art workshops, the kids wanted depictions of the beach and playful summer days.

Spanning the length of the newly-revitalized pool at Garfield Center and enlivening the natatorium with its bright colors and shapes reflected in the water, Santuario celebrates the regions from which many of the immigrants in the Mission come from.

Tell me more about how you worked with the community.

I have a lot of ties with community members in the Mission District, so I interviewed people and asked how they use the park. Elders use the park to play games, and that’s why I included an elder in the work. I led a children’s creative session and talked to neighborhood leaders to understand what they like and what colors stood out for them.

In addition to conversations with community leaders and elders, collages crafted by neighborhood youngsters during a creative workshop provided meaningful inspiration for the glass mural.

In addition to conversations with community leaders and elders, collages crafted by neighborhood youngsters during a creative workshop provided meaningful inspiration for the glass mural.

How did you get input from the children?

Children have great ideas, because they think in symbols and emotions. I gave the kids some of the shapes I use in my art and asked them to reassemble them and show me how they would represent being in the water. I asked them what symbols stood out to them, and they mentioned inflatables, balls, palm trees, and bodies of water. In my workshop, the kids created their own collages using my shapes and color palette.

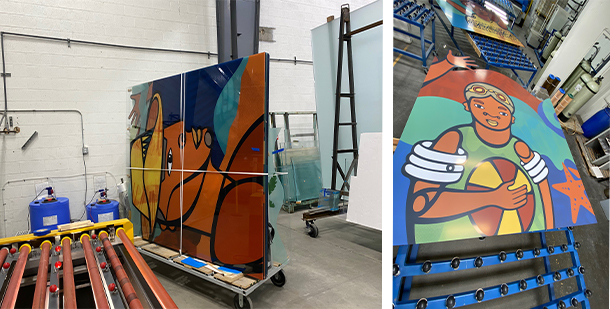

Glass panel fabrication at Pulp Studios entailed multiple tests and adjustments.

What was involved in fabricating the piece?

I started with my conceptual drawings. My collages were about a tenth of the size the completed versions would be. I partnered with Pulp Studios, a manufacturer of specialty and decorative glass products in Gardena, California, and they were excellent. We recreated every single glass pane digitally to match my concept, and we did multiple printings on glass so I could test out the translucency and color. This process involves digitally printing on glass that is run through ovens in 4' x 8' sheets, then installed onsite. I learned that not all colors work equally well on glass. For example, I had to remove all my pinks. I wanted light to be able to shine through the glass and create textures on the pool itself, so getting the right level of translucency was critical.

Mural panels arriving at the Garfield Center construction site (left) and after final installation (right).

Was this your first glass project?

This was my first glass project and my first public art project.

It seems like your values really align with those of public art. Is this an area you’re looking to expand into?

Yes. I want to have my art be more accessible to everyday people where it can be seen by everyday people. This project gave me the confidence to apply for other city projects and I’m proud to share that I just completed an even larger work for San Francisco Animal Care and Control, and part of it incorporated glass. Having the Garfield Center project under my belt made me a competitive candidate for the pet shelter project.

A colorful installation in the new San Francisco Animal Care and Control at 1419 Bryant Street – another public art project of the San Francisco Arts Commission – celebrates the diversity, beauty and dignity of all living creatures.

This is a really interesting time. There’s a reckoning around social justice and equity for people of color. What are your thoughts about the role of the artist in community building and in addressing social issues?

I grew up in a community that was impacted by the war on drugs and by mass incarceration. I was raised in the 1980s and 1990s, when Oakland, California was a very hard place to live in. I witnessed the birth of the anti-immigrant movement here, and I’m the daughter of immigrants.

The reason I became an artist is because I did not see myself reflected in the culture around me. I didn’t see the stories of Latinx people, of immigrants, and I knew I had a gift. I’ve been an artist since I was a kid, and my parents encouraged me as much as they could, although they didn’t really understand what I was doing. For me, art is a language that is about empathy and understanding, that helps us connect with each other’s experiences. It’s very sad to me that most museums I go to have collections that are 85 percent white male artists. It’s upsetting to me that there are a number of barriers that I face as a woman of color artist. That reflects a disinterest and a disinvestment in the cultural expression of my community. For me, the arts is a way to address that and to bring my perspective to everything I create.

When I created this mural, I knew that when kids saw it they would connect to the imagery and the colors. I felt that it would remind them about the colors in their own homes.

I think that art is tremendously powerful in shaping ideas and shaping societies. If more people are exposed to art—films, TV shows, books, plays, visual art—that are created by members of marginalized communities, they can understand these communities better, and they wouldn’t be allowing hateful policies against them. For example, if more of us grew up with Muslim culture represented around us, I believe we would do better in standing against Islamaphobia.

My goal as an artist is to help show the reality of our beautiful communities, to leverage art as a language of connection, and to open doors for other artists, because I’m one of the few Latina artists who is doing public art projects. There are very few of us, and that has to change.