By Douglas Tom and Andrew Wolfram

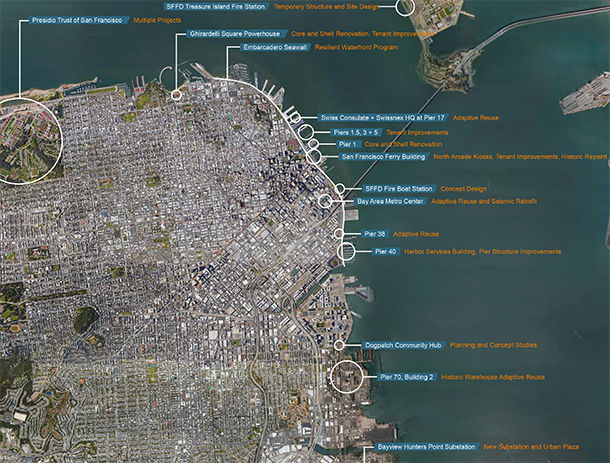

TEF’s story is intimately linked with San Francisco’s waterfront. Two of the firm’s very first projects, both started in 1999, involved designing properties along the Bay. The first was the Ferry Building, for which we did the as-built drawings for Simon Martin-Vegue Winklestein Moris (SMWM). Andrew was a project architect at SMWM at that time, and you can read his account of his history with that building over the years at https://tefarch.com/dialog_detail/43. Our second project—also with SMWM—was a partial conversion of Pier 1 from a dilapidated sugar warehouse to the headquarters of the Port of San Francisco.

The rehabilitation of the iconic Ferry Building catalyzed the revitalization of the waterfront. Anchoring the terminus of Market Street, the restored elevation along the Embarcadero (top) comes to life on the weekend at the famous Farmers Market, bringing locals and visitors to the water along the Port Walk (above left). TEF subsequently integrated a system of modular kiosks to activate the North Arcade with local artisanal offerings (above right).

Both of these projects involved public-private partnerships, which were relatively novel at the time, as well as historic tax credits and both played key roles in kick-starting waterfront development in San Francisco and setting the standard for historic renovation along the Bay’s edge. They also both provided much-needed public access to the waterfront, which had long been separated — visually and physically — from the rest of the city until the demolition of the Embarcadero Freeway in the early 1990s.

Providing access to the water is key in all of the work we’ve done. At the Port of San Francisco Headquarters at Pier 1, the route through the lobby follows the historic rail tracks that once served the Port of San Francisco’s rail service, offering great views to the waterfront. The redevelopment of the Ferry Building cleared out a warren of dimly lit offices inserted in the 1950s to reopen expansive views to the waterfront. A generously sized walkway was added that stretches around the Ferry Building to bring people close to the water’s edge.

Pier 1 Port Walk extension (top), entrance (above left), and bulkhead interior (above right) through which trains once pulled their cars to the water’s edge to load and unload its cargo.

Our next waterfront project, Piers 1½ , 3, and 5, started in 2001 and extended the public promenade from the Ferry Building, wrapping it around historic piers adapted to house a mix of offices, restaurants, and cafes. This was the largest project the firm had taken on to date. That same year, we also started work on the South Beach Harbor Services Building, a new structure that was part of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency’s revitalization of Pier 40, to the north of what was then called AT&T Park. This project involved replacing the existing Harbor Master Building and adding a new public park.

More recent projects of ours include the Swiss Consulate/Swissnex at the east end of Pier 17, which houses the Consulate General of Switzerland as well as government, education, business, and innovation partners. The building features a large, operable glass garage door at the pier’s end, leveraging spectacular views of the water.

Pier 3 and 5 along the Embarcadero (top), Bayside improvements bring people to the water’s edge along the Port Walk at Pier 3 (above left) and into direct contact with the Bay at Pier 5, when the water laps onto the concrete promentories at high tide.

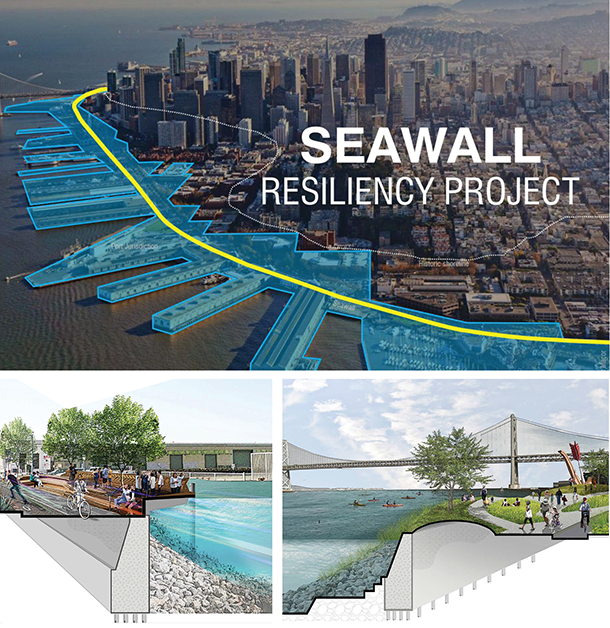

In recent times, protecting the waterfront from the effects of climate change has become another dominant theme. For the last five years, we’ve been working with the Port of San Francisco to adapt the Embarcadero Seawall to resist earthquakes and better deal with rising sea levels. Sea levels are anticipated to rise up to five feet by the end of this century, and if a major earthquake strikes, damage to the seawall could potentially inundate downtown San Francisco.

New and existing private development along the waterfront also has to address sea level rise. The redevelopment of Pier 70, which we’ve been involved with recently, will create a 28-acre neighborhood on a historic shipyard as part of a public-private partnership. The plans call for new housing, office space, parks, space for artists and local manufacturing, and rehabilitated historic buildings. The site was extensive enough that it was possible to lift new buildings and even some of the historic ones above the ground plane to protect them from rising seas. But the historic core is still at original grade, so some kind of defensive mechanism will need to be put into place to protect those buildings.

The Harbor Master’s Building at Pier 40 (top) houses the Pier 40 Yacht Club, a community multipurpose room, and public recreational amenities including boat repair and locker rooms. The second phase of the project encompassed the rehabilitation of the historic shed building (above).

The Harbor Master’s Building at Pier 40 (top) houses the Pier 40 Yacht Club, a community multipurpose room, and public recreational amenities including boat repair and locker rooms. The second phase of the project encompassed the rehabilitation of the historic shed building (above).

Waterfront work is always complicated. For one thing, utilities run underneath the pier decks, so repairs can only be performed at low tide, when that space is accessible. To protect birds in nesting season and herring in spawning season, certain times of year are off limits for construction. Then there are a myriad of different agencies and entities to gain approvals from, including the United States Army Corps of Engineers, the California State Lands Commission, and the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC). Plus the public is always interested—rightly so—in whatever is being planned for the waterfront.

A “Swiss House on the Bay,” the Swiss Consulate/Swissnex is housed at the east end of Pier 17 (top). Its large operable garage door (above) exploits stunning views across the water.

Andrew has also been a member of the BCDC’s design review board for the past few years, which has given him a front-row seat to a number of major projects that are happening around the Bay, in cities like San Francisco, Oakland, and Richmond. One way the design review board advocates for the public is by nudging private developers to add more public space and offer greater access to the water’s edge, while ensuring that the waterfront feels open and welcome to everyone. Design plays an important role in inviting groups that have typically been underrepresented in waterfront areas. That means making sure that developers incorporate design cues that make open spaces feel truly public, rather than reading like something set aside just for occupants of a particular development.

The adaptive reuse of Building 2 at Pier 70, part of the Union Iron Works Historic District, transforms a WWII era concrete warehouse for office use. The six-story concrete building sits at the heart of the area’s development, at the terminus of a public open space promenade that extends westward from the bay.

There are so many possibilities ahead for San Francisco to keep enhancing waterfront access. We can improve bicycle and pedestrian trails, perhaps as part of enhancing the sea wall. We can establish areas with softer, more natural edges at the land/water interface, improving aesthetic appeal while also providing better habitats for wildlife. And the waterfront hasn’t historically been as family friendly as it could be, but that’s starting to change, with places like Crane Cove Park, which opened two years ago. South of the Bay Bridge, the Port of San Francisco is also constructing China Basin Park, a five-acre recreational centerpiece for the planned Mission Rock neighborhood.

As part of the team lead by CH2M HILL Companies, Ltd. and Arcadis, TEF collaborated closely with CMG Landscape Architecture to catalog and analyze historic assets and urban design features and their vulnerability to earthquakes and sea level rise and to develop strategies for adaptation and preservation.

San Francisco has retained more historic buildings along its waterfront than most other cities, a tremendous resource for the region. Over the last couple of decades, we’ve watched the city make significant changes, preserving heritage while connecting residents and visitors to new uses. Much remains to be done to fill in the gaps, restore empty and underused historic structures, and protect the progress we’ve made. Fortunately, a whole new wave of ingenuity is on its way.